Researchers Investigate Strange Space Weather That May Have Interrupted Early Humans 41,000 Years Ago

Three researchers: an archaeologist who studies past civilizations and their interactions with their environments, and two geophysicists who explore how solar activity affects the Earth’s magnetic field, came together to perform an interesting and ambitious study. However, initially, the concept of connecting space with human behavior seemed impossible, as it bridges two different fields of the scientific world. But two years later, this collaboration paid off in many ways, professionally and scientifically. Their work was recently published in the journal Science Advances.

Earth’s Magnetic Shield

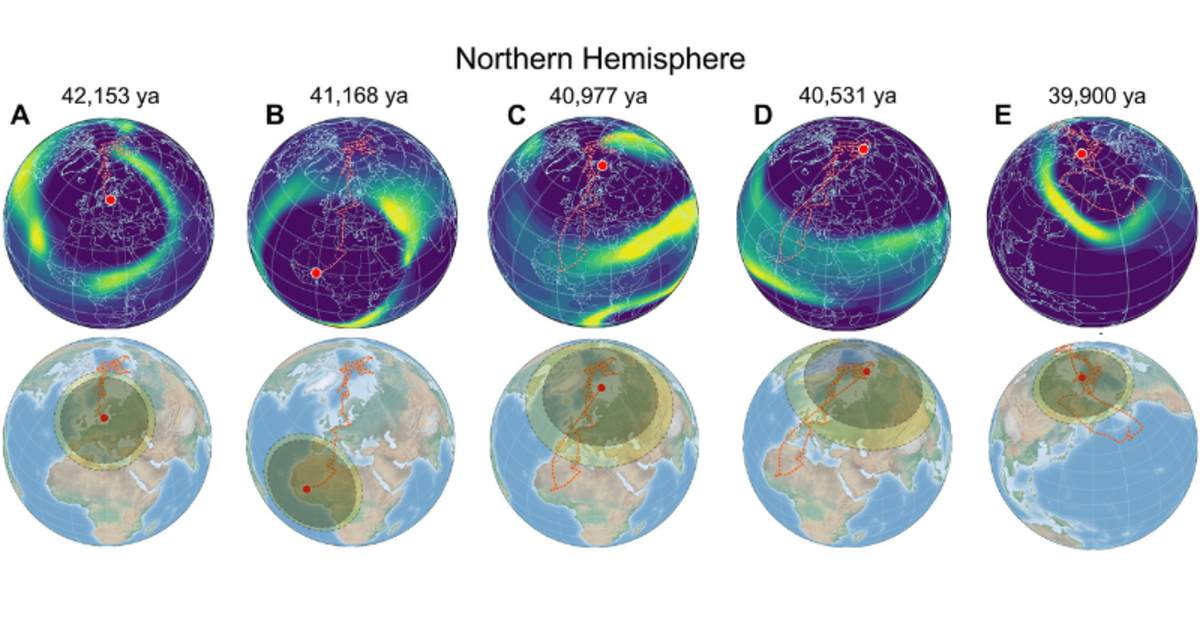

The researchers focused on the mysterious incident when the planet’s magnetic field collapsed over 41,000 years ago. This collapse is known as the Laschamps Excursion, a short yet extremely large geomagnetic event first identified in the volcanic fields in France. During the Laschamps Excursion near the end of the Pleistocene epoch, the Earth’s magnetic poles didn’t reverse like they do every hundred thousand years. Instead, they moved erratically and quickly over thousands of miles. The strength of the magnetic field at the same time dropped to less than 10% of its modern era intensity. The magnetic field during the event weakened significantly, and its dipole structure fractured, leading to multiple scattered magnetic poles across the planet, according to The Conversation.

The protective field, referred to as the magnetosphere, became distorted and leaky. The magnetosphere usually deflects much of the solar wind and the ultraviolet radiation that is harmful to human beings from the Earth’s surface. But when it was weakened, the models showed that the effects near Earth would have been extreme. Although there is a need for more research to fully understand the impact, as auroras, typically seen near the poles, would have moved towards the equator, and the radiation levels would have been even higher than modern-day levels. The skies 41,000 years ago may have been both spectacular and threatening. “When we realized this, we two geophysicists wanted to know whether this could have affected people living at the time,” noted geologists Agnit Mukhopadhyay and Sanja Panovska.

Weird space weather seems to have influenced human behavior on Earth 41,000 years ago – our unusual scientific collaboration explores how https://t.co/8J5FlMIaGg

— The Conversation U.S. (@ConversationUS) July 20, 2025

The Archaeological Approach Behind the Study

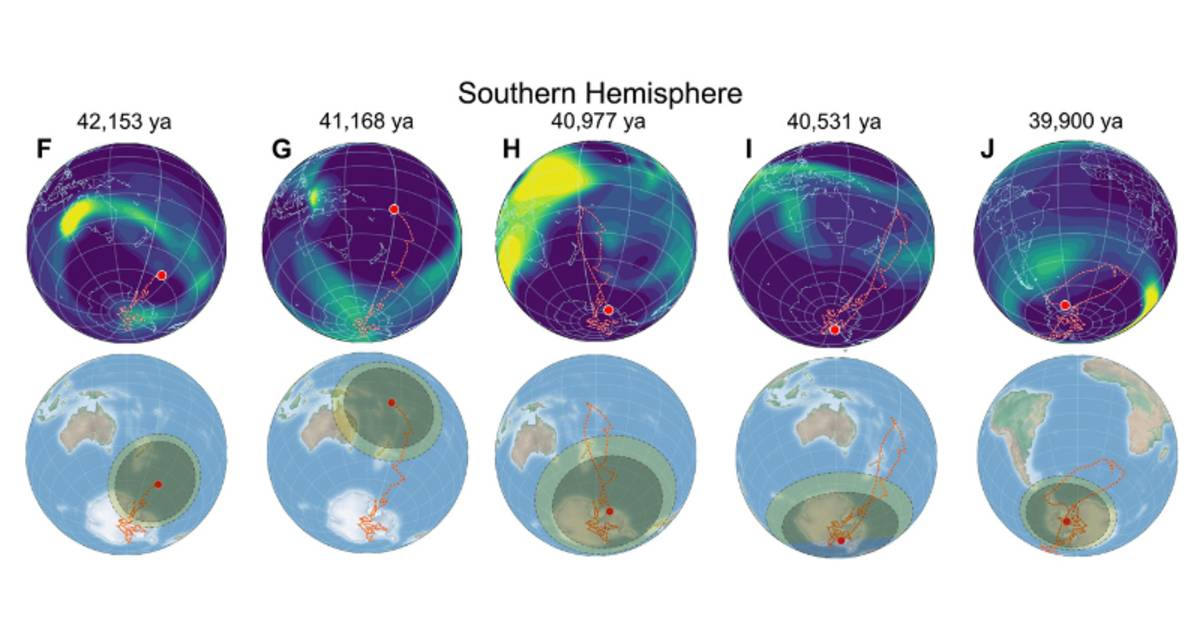

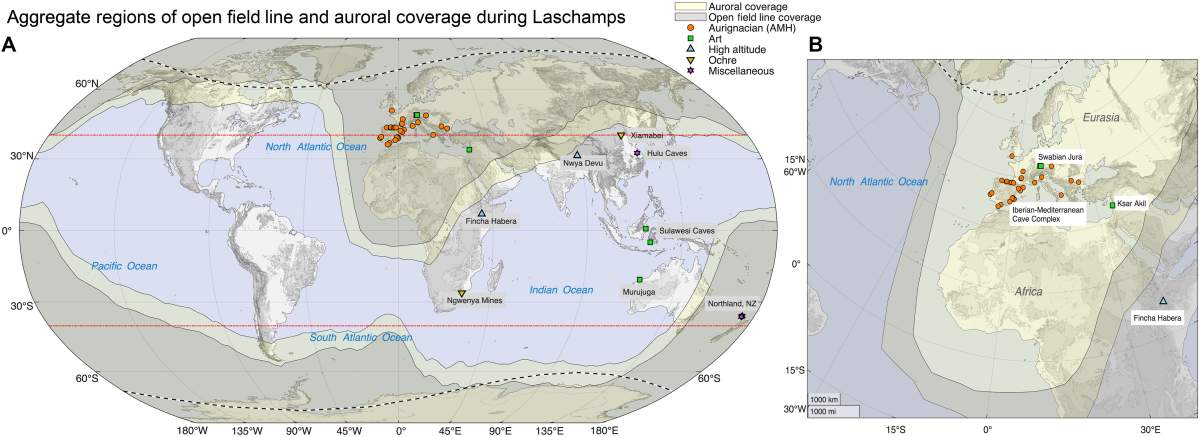

For people during that time, the experience of an aurora might have been filled with awe, fear, ritual behavior, or much more. But the archaeological record for understanding this is far too limited to capture these cognitive and social responses. Researchers are clearer about the physiological effects of increased UV radiation. The weakened magnetic field meant more harmful radiation reaching the Earth’s surface and leading to higher risks of sunburn, eye damage, birth defects, and a myriad of health issues. The archaeologist on the team believed that in response, people might have taken more practical approaches.

People at that time spent more time in caves, wore clothes tailored for better coverage, or even applied a prehistoric version of sunscreen made of ochre. “As we describe in our recent paper, the frequency of these behaviors indeed appears to have increased across parts of Europe, where effects of the Laschamps Excursion were pronounced and prolonged,” noted the team. Different populations of the human species, from Neanderthals to Homo sapiens, exhibited different approaches to environmental changes, with some relying on shelter or material culture for protection.

“We’re not suggesting that space weather alone caused an increase in these behaviors or, certainly, that the Laschamps caused Neanderthals to go extinct, which is one misinterpretation of our research. But it could have been a contributing factor—an invisible but powerful force that influenced innovation and adaptability,” explained Raven Garvey.

The Future of the Study

The researchers noted that bridging the two disciplines of archaeology and geophysics initially felt daunting but has now turned out to be incredibly rewarding. Archaeologists in their studies trace invisible forces, like climate. They are now beginning to see space weather as a part of the story. For geophysicists, the link with archaeology adds a human lens showing how the effects of space don’t just stop at the Earth’s surface but trickle down to the people and other forms of life on Earth. “Our unconventional collaboration has shown us how much we can learn, how our perspective changes when we cross disciplinary boundaries. Space may be vast, but it connects us all. And sometimes, building a bridge between Earth and space starts with the smallest things, such as ochre, or a coat, or even sunscreen,” the team concluded.