Brain doesn't update 'body map' after losing a limb: Study

Brain functions are an intriguing area to explore for experts. For decades, researchers have been exploring the human mind, yet they have not understood it fully. When new research comes in, it changes the picture of the brain's inner workings from the previous studies. The latest one has been explained in the journal Nature Neuroscience, as it claims that once the brain conceptualizes a map of the human body, it remains unchanged, even if the individual suffers anatomical loss. If the assertion is true, then that would challenge several decades-old assumptions.

Map Formed by the Somatosensory Cortex

The human brain's somatosensory cortex holds a detailed map of the human body, according to IFLScience. Different portions of the cortex represent distinct parts of the human body. The map's objective is to help the brain process sensory information from the environment. The portions in the cortex linked to particular parts will only respond to simulations received by those parts. After processing, the brain develops a picture of where the sensations are coming from and which body part it is impacting. For years, researchers thought that this map updated itself if the individual lost a limb. Essentially, the cortex's portion linked to that limb will no longer feel anything from that particular part. But phantom limb sensations experienced by 85% of amputees made several experts think otherwise.

Cause of Phantom Limb Sensations

Phantom limb sensations are pains that people feel in their missing parts, as they are felt by the majority of amputees, to a certain extent. "Many describe their phantom limb pains as a crawling feeling on the skin, a burning, the sudden feeling of a spike driven through the missing body part, or the feeling as if their hand is clenched and won't open," Neuroscientist Dr Austin Lim explained.

Analyzing these sensations stunned researchers, as it questioned their past findings about the body map present in the brain's somatosensory cortex. Experts essentially questioned, if the limbs are not present, then how is the cortex processing sensory information from the imaginary simulations received by the missing parts? It made experts speculate that the body map remained somewhat stable, no matter the loss.

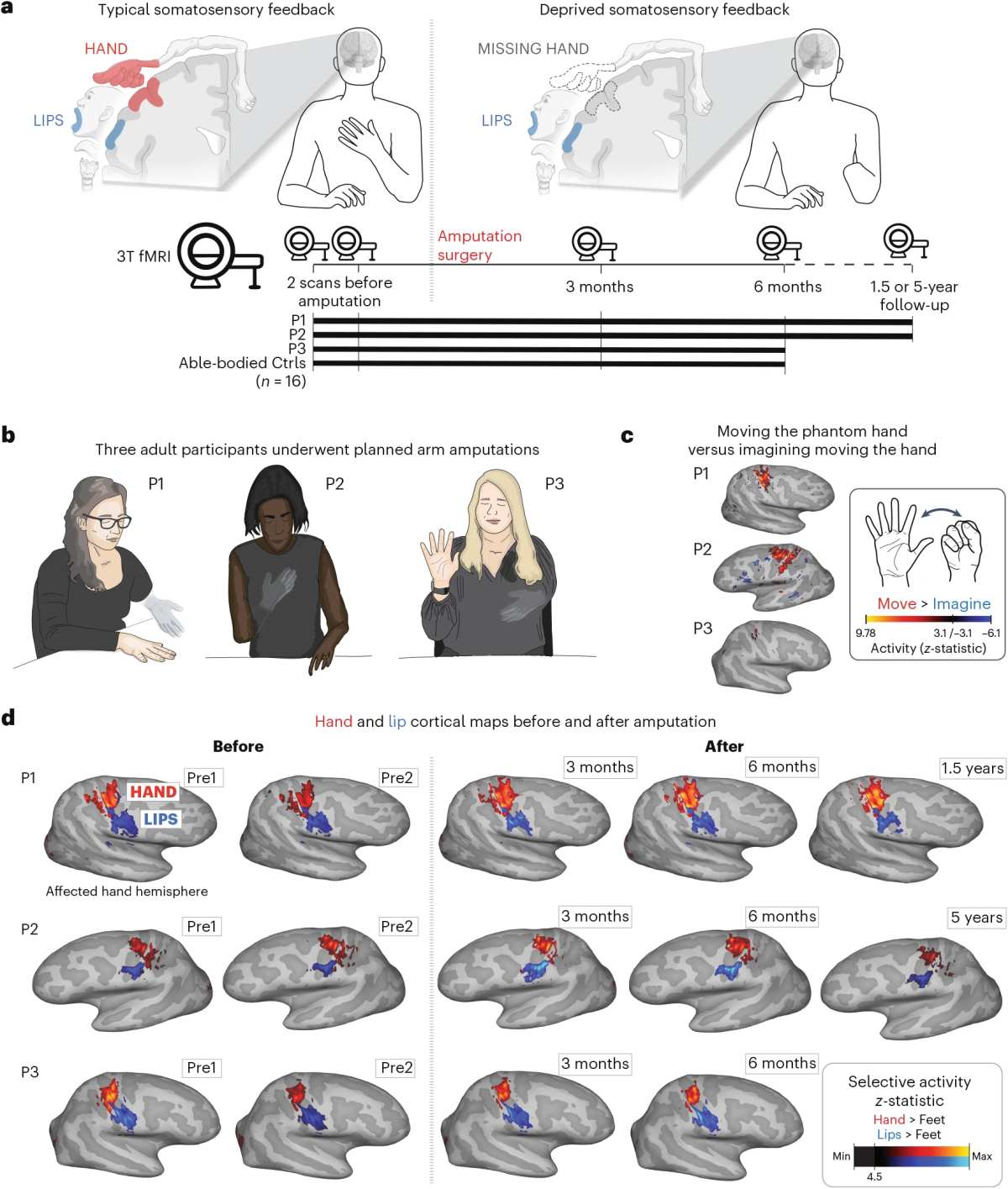

Examination of Amputees

To verify their speculation, researchers examined three people who were to undergo amputation on one of their arms, according to Scientific American. The map formulated by their somatosensory cortex was observed by experts through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) before the surgery and for five years after the operation. Before the surgery, the subjects were requested to do activities like flexing their toes, pursing their lips, and tapping their fingers during the scanning. The experts then jotted down what parts of their brains activated during the actions. In this way, researchers were able to pinpoint the portion of the brain that was associated with the hand in the map.

Past studies have implied that the maps are updated after the loss by redistribution of neighboring neurons in the region associated with the lost limb. Hence, during the scanning, researchers also noted how the brain reacted to movements by neighboring parts, like the lips. After the surgery, researchers requested them to move their "phantom" fingers during the scanning.

Results indicated that even after five years, the movement of "phantom" fingers affected the same portions in the cortex that the missing hand was once associated with. They also found no evidence of neighboring neurons entering the affected area. The finding proves that the map remains somewhat stable, and this knowledge can be used by experts to make better prosthetic limbs controlled by brain–computer interfaces in the somatosensory cortex.