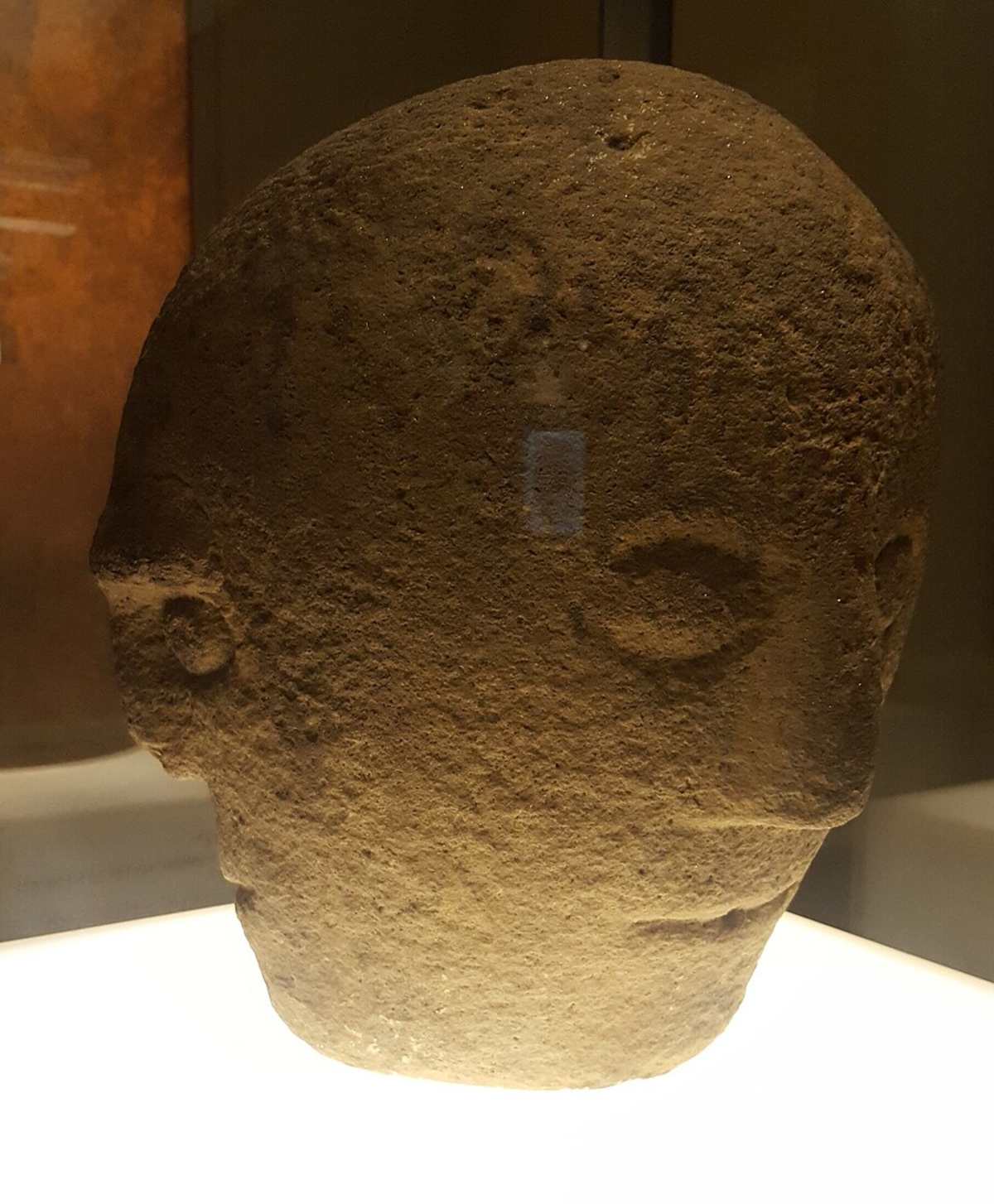

Three-headed 'Corleck Head' sculpture may have been associated with human sacrifice 1,900 years ago, experts suggest

The Corleck Head sculpture, currently housed at the National Museum of Ireland, may have links to Celtic traditions, according to Live Science. Such objects have been detected before in Ireland, but the Corleck Head is the finest of its type. Researchers believe that such objects had links with concepts like divinity and supernatural power. However, Corleck Head's exact meaning and objective remain under wraps. One speculation is that it could be a representation of the Celtic god Lugh.

Three-headed treasure

The Corleck Head sculpture was discovered in 1855 at the Irish town of Drumeague, about 60 miles northwest of Dublin. Such objects are also called tricephalic or janiform sculptures, which originated in the first century, at the hands of the Celts, as part of a pagan ritual. According to the information provided by the National Museum of Ireland, Corleck Head is around 13 inches tall. The three faces on the sculpture have broad noses and slit-like mouths. One of the mouths appears to have a small hole in the center, while another exhibits heavy brows. Experts believe that the sculpture was placed on some sort of pedestal, as the bottom of the model also has a hole. This hole may have fit into the pedestal where it was possibly displayed during a pagan ritual.

Association with divinity

The sculpture was discovered by a local historian named Thomas Barron, according to Bailleborough. He asserted that the figure had links to a shrine located at Drumeague Hill, based on Romano-British traditions. The site where the three-headed sculpture was uncovered hosted an ancient Celtic practice called the Lughnasa festival, which celebrated the harvest. It is possible that the three-faced model played a part in this practice.

Researchers speculate that items like the Corleck Head were considered a symbol of otherworldly powers and divinity to the Celtic community due to the prominence held by the head in their Iron Age culture, according to the National Museum of Ireland. The community worshipped the human head with their art, craftsmanship, and physical practices. As far as the supernatural connection is concerned, researchers cite the way decapitated human skulls were placed on Iron Age sites by the Celtic community. The placement clearly indicated that they were used in rituals and sacrifices.

The sculpture was carved out of a single block of limestone around the first or second century AD, at the end of the La Tène period in Ireland, according to Emerald Isle. Its association with the Iron Age was based on its similarities with certain stone heads found across Europe, dating back to that period. The sculpture was supposedly discovered near the "Corleck ghost house," which again strengthens its pagan links.

The three-faced Corleck Head stone idol, found at Corleck Hill, County Cavan. It likely represents either three different gods or a triple deity. The site where it was found was associated with the Lughnasa festival until the late nineteenth century. pic.twitter.com/yfZUvxXInm

— 🪙 Beothach (@GaelicRevival) December 3, 2024

Reflection of a god

Many experts believe that the sculpture depicts a female goddess, maiden, mother, and crone, in its three faces. Others believe that it may reflect omniscience, a god that sees all, the past, present, and the future. The sculpture could be a representation of a pagan god or a deity from the pre-Christian era in Ireland. Historian Jonathan Smyth identified the Celtic god Lugh in the sculpture, with its three faces representing different technologies. However, on the pillar, Lugh's sculpture was possibly displayed as a phallic symbol of fertility, considering the context of the harvest festival in which it was discovered.

Smyth's other theory is that the sculpture may have meant destruction or association with human sacrifice. This assertion arrived from the presence of a sacrificed Iron Age man in the nearby area, who had been killed by strangling, bludgeoning, and slashing. Further examination is needed to assert the original intention of this sculpture, but researchers are sure that the model was considered cursed by the time the medieval period arrived. They believe it was buried between the 10th and 13th centuries to suppress early Celtic religious traditions by the medieval Irish community.